6. Eurosystem monetary policy

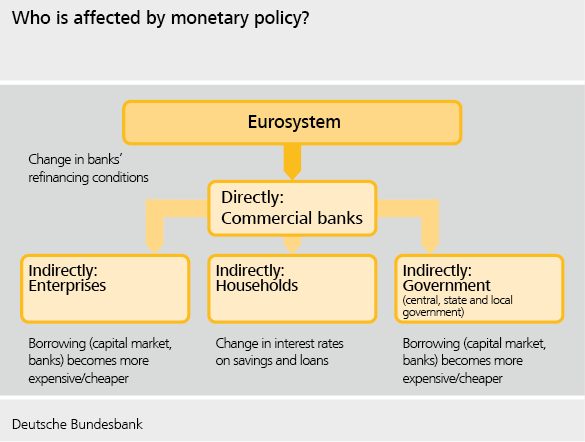

The primary objective of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy is to maintain price stability. However, to achieve this, monetary policy does not influence prices directly. The Eurosystem’s monetary policy measures only have an indirect impact on developments in the price level. The Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) decides on the individual measures based on its monetary policy strategy.

The primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain price stability.

6.1 How monetary policy works

In a market economy, the prices of individual goods and services must be free to move up and down in order to send undistorted signals regarding supply and demand conditions in the markets. In this way, the economy’s limited resources are directed to where they are needed and where they can be used most profitably. Price setting should be as free from government intervention as possible. For this reason, the central bank does not use its monetary policy to steer individual prices. Instead, it influences aggregate demand so as to have an indirect effect on the price level. The price level describes the average of all prices and – much like the prices of individual goods – is determined by supply and demand. It tends to rise if aggregate demand outpaces aggregate supply. In the opposite scenario, the price level declines.

Monetary policy influences the price level indirectly via aggregate demand.

Interest rates play an important role in aggregate demand. Higher interest rates increase the incentive to save and make borrowing more expensive. If this results in less money being spent, i.e. fewer goods or services are purchased, this tends to have a dampening effect on aggregate demand and thus on price developments. Conversely, lower interest rates tend to lead to rising (and also credit-financed) demand and consequently to higher prices.

Interest rates in the credit and capital markets therefore have an important signalling and steering function in that they represent prices for borrowing or remuneration for saving. However, they are not determined directly by the central bank. Rather, traditional monetary policy instruments focus on the interest rates at which the commercial banks borrow central bank money from the central bank. Changes in these interest rates have an indirect impact on interest rates in the credit and capital markets and therefore ultimately on aggregate demand, too.

Starting point for monetary policy: the need for central bank money

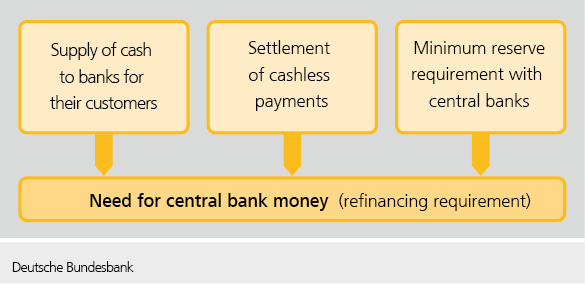

An important starting point for monetary policy is commercial banks’ need for central bank money – that is, the book money commercial banks hold on their accounts with the central bank as well as the currency in circulation. There are three reasons they require this funding: the demand for cash, the settlement of cashless payments via central bank accounts, and the requirement of maintaining a minimum reserve on their accounts with the central bank.

Bank customers request central bank money in the form of cash to use to pay for their purchases or as a store of value. They generally receive cash from commercial banks – by withdrawing it from ATMs, for instance. Banks have to obtain the cash required for this purpose from the central bank by having the cash paid out from the balance on their central bank account.

In addition, commercial banks require central bank money to settle cashless payments. Commercial banks usually execute such payments via accounts held with the central bank. However, banks can effect transfers to one another only if they have a sufficient balance of funds on their central bank account.

Central banks may also require commercial banks to maintain a minimum reserve, meaning that a commercial bank must hold a minimum balance on its account with the central bank. Banks’ need for central bank money also stems from this (see Section 6.3.1).

Only the central bank can create central bank money. This monopoly position is an important lever for monetary policy. Banks usually obtain central bank money in the form of loans from the central bank. The lending central bank credits the loan amounts to the commercial banks in the form of deposits on their central bank accounts. The commercial banks have to pay interest on the loans. The level of this interest rate indirectly influences all other interest rates in the financial system via what is known as the transmission mechanism. It is therefore called the “policy rate”.

The interest rate on central bank money is called the “policy rate”, as it affects all other interest rates.

The money market

Although every commercial bank needs central bank money, not all euro area commercial banks participate in the loan-based procedures used by the Eurosystem to provide it (referred to as central bank refinancing operations). Most banks leave this to the larger institutions, which subsequently lend a portion of the central bank money they receive to other banks, subject to interest. The market where the supply and demand for these interbank loans in central bank money meet is called the market for central bank money, or simply “the money market”. The rate of interest paid on central bank money traded between commercial banks also has a signalling function. It reflects whether central bank money in the banking sector as a whole is readily available (indicated by an interbank rate below the main refinancing rate) or rather scarce (indicated by an interbank rate above the main refinancing rate; see Section 6.3.3, “Money market management”).

Overnight money is the form of money most frequently traded in the money market. These interbank loans involve commercial banks with a surplus of central bank money lending a certain amount to other commercial banks in need of central bank money. The maturity of such operations is only one day. Overnight money, then, refers to overnight loans which are already paid back the next day, with interest. However, alongside overnight money, interbank loans with maturities of one week, or one or several months, are also traded in the money market.

Up until the onset of the banking and financial crisis in 2007-08, commercial banks had mostly granted unsecured loans in the money market, meaning that they did not demand any special loan collateral from their borrowers. However, once there were suddenly fears that banks could become insolvent overnight, this form of loan trading temporarily dried up. Lending between commercial banks has since recovered, but secured loans remain the norm.

The transmission mechanism

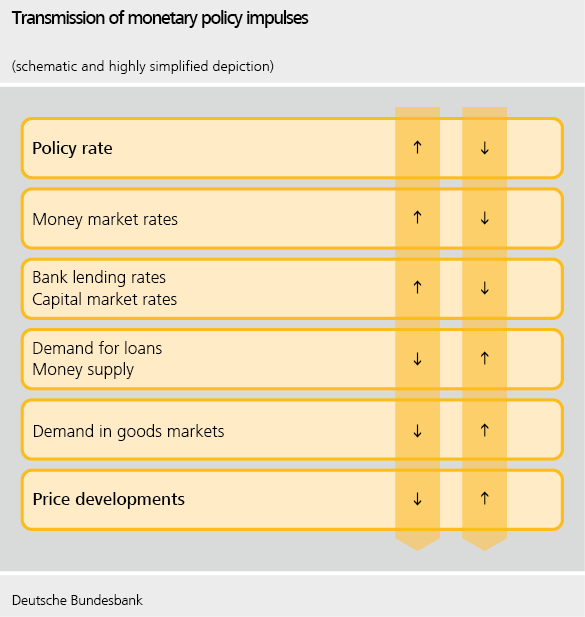

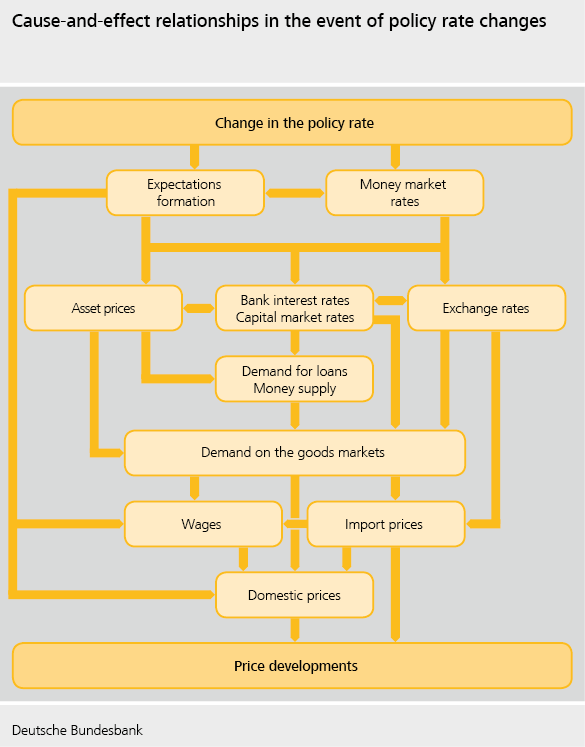

Traditionally, central banks try to ensure monetary stability by adjusting their policy rates. This simplified depiction of the transmission mechanism illustrates how a change in the policy rate usually affects price developments and thus the rate of inflation.

The starting point of the monetary policy chain presented here – the “interest rate channel”, as it is called – is the interest rate (i.e. the price) set by the central bank at which banks can borrow money from the central bank. If the central bank raises the policy rate, interest rates in the interbank market (money market) usually increase as well. The interbank market is where central bank money is traded between commercial banks in the form of account balances held with the central bank. Banks usually pass on the higher price of central bank money to their customers by raising their interest rates on corporate and personal loans. Demand for such loans generally declines when these bank loans become more expensive. As a result, credit-financed demand for goods and services in the economy weakens. In such an environment, enterprises have less scope to push through price increases. Consequently, aggregate inflation is dampened and the inflation rate declines.

The monetary policy transmission process begins with a change in the policy rate.

The opposite holds true if the central bank lowers its policy rate: it becomes cheaper for enterprises and households to take out bank loans, which in turn stimulates enterprises’ credit-financed investment activity and, at the same time, boosts consumers’ demand for durable consumer goods. Aggregate demand rises. Enterprises can increase their prices both more easily and by a greater amount. The rate of inflation tends to rise.

Impact of policy rate changes on capital market rates

In the capital market, large enterprises and government bodies obtain long-term financial resources by selling bonds (also known as debt securities) and thus taking out loans. The issuer of the bond pays the buyer (holder) interest on a regular basis. Upon maturity, the bond is bought back (redeemed) by the issuer. Bonds are traded daily on stock exchanges.

Capital market interest rates do not necessarily follow the change in the policy rate.

Long-term capital market rates, i.e. interest rates in the bond market, do not always change in line with policy rate changes. If, for example, the central bank lowers its policy rate, long-term capital market rates do not then necessarily fall to the same extent. They could even rise if investors fear that the policy rate cut will lead to higher inflation in the medium term. In such a scenario, investors will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the anticipated decline in purchasing power of their investments caused by the rise in inflation. The central bank must also consider the possibility of this undesirable response when deciding which monetary policy instrument to use and the extent to which it should be deployed. If the central bank’s monetary policy decisions are to have the desired effect on the interest rate level to the greatest degree possible, this crucially depends on its credibility and stability-oriented stance.

Exchange rate effects

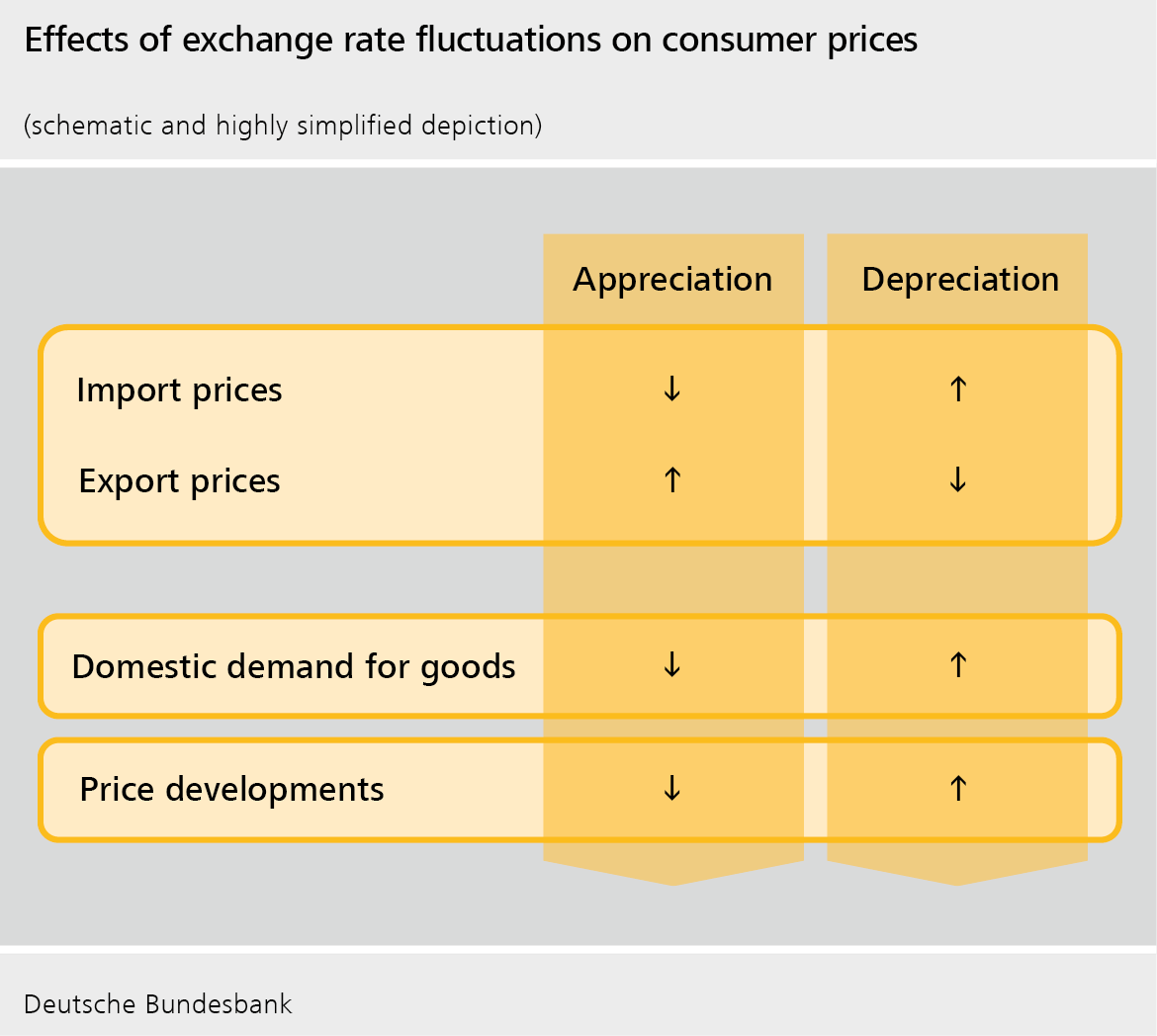

Another important transmission channel of monetary policy is the exchange rate channel. The exchange rate is the price of one currency expressed in units of another currency. This also reacts to changes in monetary policy. For instance, if domestic interest rates outpace foreign interest rates, investment in the domestic capital market tends to become more attractive – for both domestic and foreign investors. This leads to higher demand for domestic currency, which consequently becomes more expensive relative to the foreign currency, provided that the exchange rate is not fixed by the government. The process is reversed if domestic interest rates fall compared with foreign interest rates.

Exchange rate fluctuations also affect demand and thus price developments.

Exchange rate changes like these have an impact on aggregate demand and therefore on developments in the price level, too. If, for example, the euro gains in value against another currency (appreciation of the euro), products from the other currency area become cheaper for buyers in the euro area (decline in import prices), with the result that demand for these products increases. As a result, euro area demand for goods produced within the euro area tends to decline, dampening price pressures and therefore the inflation rate. At the same time, foreign consumers have to pay more for euro area goods priced in foreign currency following an appreciation of the euro (i.e. export prices increase). Foreign demand for such goods thus also tends to decline, which then also dampens price inflation in the euro area.

The opposite is true if the euro loses value against another currency: from a euro area perspective, imports of foreign goods become more expensive (i.e. import prices increase), dampening demand for these goods. In turn, therefore, demand for domestic goods tends to rise. The result of this is that domestic prices, and hence the inflation rate, increase. At the same time, the depreciation of the euro improves sales opportunities for exports (i.e. export prices decrease). Subsequently, foreign demand for euro area goods increases, too, which also results in higher prices and a rising inflation rate.

The impact of monetary policy is not always easy to predict

The monetary policy transmission process is complex. There are multiple transmission mechanisms that can influence one another in a variety of ways. Some of these processes are fast: for example, financial markets usually respond immediately to changes in the policy rate. However, it often takes banks a while to pass on a policy rate cut to their customers in the form of lower lending rates. Furthermore, the speed at which aggregate demand and prices change is not only dependent on the change in the policy rate. Many other factors are also relevant, such as developments in the global economy and the intensity of competition. In addition, the behaviour of enterprises, consumers, banks and governments is subject to constant change.

A central bank must always bear in mind the long and variable time lags before monetary policy takes effect and act in the most forward-looking manner possible. For the Eurosystem, in particular, this places great demands on monetary policymakers’ analytical capacity, as the individual euro area countries have different financing practices, business cycles and economic structures.

Inflation expectations

The public’s inflation expectations are of particular significance from a monetary policy perspective. If prices have increased and people expect a persistent rise in inflation, trade unions will typically try to counteract the expected loss in purchasing power by negotiating higher wages. As a consequence, enterprises will attempt to pass through the higher wage costs to the prices of their goods and services. In the worst-case scenario, a price-wage spiral can emerge, in which prices and wages drive each other up. If this causes a permanent and significant rise in inflation, the objective of price stability is jeopardised.

The expected level of inflation therefore has a considerable impact on the actual level of inflation in the medium term. Monetary policymakers must therefore employ convincing stability policy and transparent communication to instil confidence that money will maintain its value. Here, the key is to maintain inflation expectations in line with the objective of price stability.

The credibility of a central bank can also be measured by how high the public’s inflation expectations are. If credibility is high, inflation expectations are anchored at the target level of price stability.

6.2 The monetary policy strategy

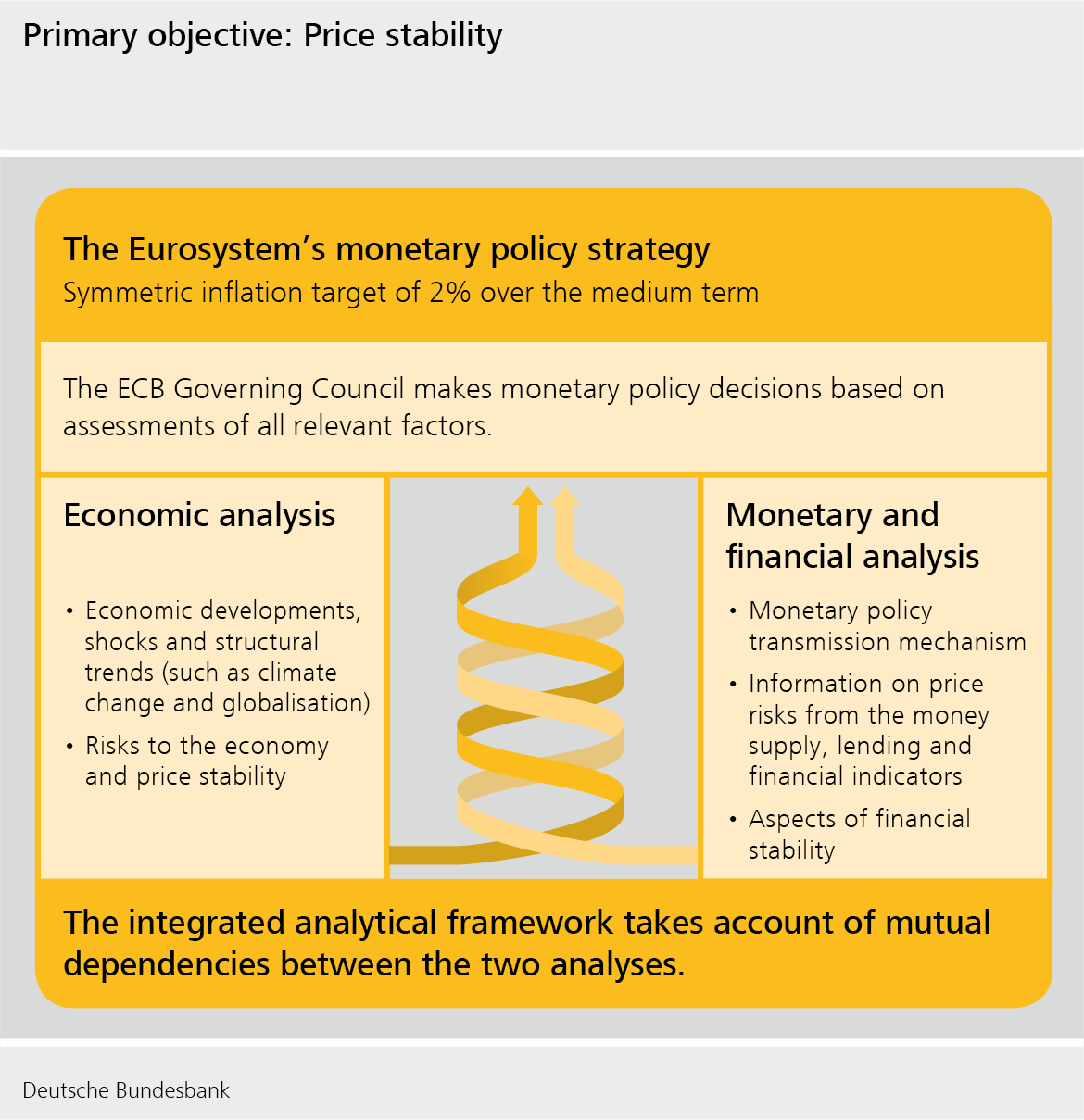

In order to achieve its primary objective of maintaining price stability in the Eurosystem, the ECB Governing Council follows a monetary policy strategy. It defines the objective and details which monetary policy instruments and indicators are suitable for this purpose. The strategy thus stakes out a systematic framework within which the ECB Governing Council takes monetary policy decisions. At the same time, it serves to explain monetary policy decisions clearly and comprehensibly to the general public.

The Governing Council published its new monetary policy strategy in July 2021. A key element is the symmetric inflation target of 2% over the medium term. Symmetry means that negative and positive deviations of inflation from the target are equally undesirable (see Section 5.4). The Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) remains the appropriate measure for assessing the achievement of price stability in the euro area (see Section 5.2).

The primary monetary policy instrument of the Eurosystem is the set of ECB policy rates. Where necessary, the ECB Governing Council may use other instruments such as asset purchase programmes, longer-term refinancing operations and forward guidance (see Section 6.3).

The Governing Council published its new monetary policy strategy in July 2021.

In future, the Eurosystem will take account of the implications of climate change as part of its mandate. Although the responsibility for climate action primarily lies with policymakers, climate change also has implications for macroeconomic price developments. In addition to the comprehensive incorporation of climate factors in its monetary policy assessments, then, the ECB Governing Council has decided to adapt the design of its monetary policy operational framework in areas such as risk assessment, asset purchases and the collateral framework.

The basis for the Governing Council’s monetary policy decisions is an integrated assessment of all factors relevant to price movements. For this, it relies on two interdependent streams of analysis: economic analysis and monetary and financial analysis. As part of this integrated analysis approach, the ECB Governing Council also examines the proportionality and potential side effects of its monetary policy decisions. The analysis is accordingly broad in scope.

The Eurosystem’s integrated analytical framework

In its economic analysis, the Eurosystem forms a comprehensive picture of the economic developments that are significant for the inflation outlook on the basis of a wide range of macroeconomic indicators.

The ECB Governing Council bases its monetary policy on two complementary analytical approaches.

The monetary and financial analyses focus on monetary policy transmission from the central bank via the financial sector through to the real economy. In addition, risks to price stability that may result from monetary and financial factors are also analysed.

The integrated analytical framework takes into account the many and varied interdependencies between economic, monetary and financial developments. The overall result is a strong and comprehensive picture that aids in the early and reliable identification of inflation risks.

Economic analysis

The aim of economic analysis is to be able to produce a comprehensive estimate of future price developments and to identify potential risks to monetary stability beforehand. To this end, economic development is observed on a continuous basis. Factors that could jeopardise price stability include, for example, economic developments (interaction between supply of and demand for goods), the domestic cost situation (wages and wage negotiations) and the external environment (exchange rates and commodity prices). A distinction is made between the first-round and second-round effects of price changes. The economic analysis also takes into account structural trends with implications for the economy (e.g. globalisation, demographic ageing, digitalisation and climate change). Moreover, financial market prices and corresponding surveys provide indications of economic agents’ inflation expectations.

The aim of economic analysis is to identify risks to price stability at an early stage.

Furthermore, the Eurosystem’s macroeconomic projections provide a comprehensive picture of current and prospective economic developments. These projections are produced jointly by experts from the ECB and the national central banks twice a year and are published in June and December. The projections are updated by ECB staff in March and September every year.

The projections centre on forecasts of macroeconomic performance (gross domestic product) and consumer price movements (as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices). The term “projection” indicates that this is the result of a scenario based on a number of assumptions – for example, regarding oil prices or exchange rate developments.

First-round and second-round effects

In monetary policy analysis, a distinction is made between first-round and second-round effects. First-round effects show the impact of changes in the prices of individual goods or services on general price developments. Take a rise in crude oil prices, for example: the result is a direct increase in the prices of many oil products, such as petrol (direct first-round effect). However, this increase in crude oil prices also leads to higher prices for other goods and services for which oil products represent an important cost factor, such as air travel (indirect first-round effect).

Nevertheless, it is by no means certain to what extent and for how long a rise in crude oil prices will affect downstream prices. First, this depends on factors such as the country’s economic situation as well as the market power of the enterprises concerned, i.e. how easily enterprises are able to pass through higher costs to consumers by raising prices. Second, consumers’ responses to price increases also play a role. It depends on whether consumers cut back their consumption of products and services that now cost more or replace the more expensive goods with other, cheaper ones, or whether they do not change their consumption habits and reduce their savings or accumulate debt to finance the increased expenditure.

Monetary policymakers are not usually in a position to influence the original first-round price change or the ensuing effects on the inflation rate. Many central banks therefore take the approach of “looking through” these first-round effects. In other words, they focus on the general price trend instead. The fact that first-round effects have only a temporary impact on the inflation rate is also relevant in this context. This is because a one-off price change can no longer be measured in the inflation rate after one year, as this rate measures the price change over a 12-month period.

However, monetary policymakers must observe whether the first-round price changes entail any subsequent second-round effects that can lead to a sustained increase in the rate of inflation. Second-round effects represent market participants’ reactions to the first-round price increase. The focus here is on developments in wages. If, for example, trade unions strive to offset the loss in purchasing power resulting from higher crude oil prices by substantially raising wages, there is the danger of a price-wage spiral emerging. In such a case, rising prices and wages would drive each other up, potentially resulting in further accelerating inflation.

Monetary and financial analysis

At the beginning of monetary union, monetary analysis primarily focused on the fact that there was a fairly close, broadly evidenced relationship between monetary growth and inflation in the long term. Subsequently – in very simplified terms – excessive growth in the money supply led to an excessive general rise in prices in the long run. However, the money price relationship has weakened in the environment of low and relatively stable inflation rates in recent years. The direct informative value of monetary growth as an indicator of future price developments has therefore also diminished in the euro area.

Monetary and financial analysis particularly focuses on the transmission mechanism.

Nonetheless, monetary and financial variables still contain important information about potential inflation risks. This not only applies to developments in the money supply and its components, but also to banks’ lending and other financing conditions and financing structures in the economy. However, the relationship between these determinants and the price level are complex and therefore require thorough analysis. For this reason, the Eurosystem uses a wide range of models to derive information on future price risks from the development of these variables.

Aspects of financial stability are taken into account in monetary and financial analysis, too.

Monetary analysis has evolved continually since the start of monetary union and has been supplemented by financial aspects – hence why the Eurosystem has referred to it as monetary and financial analysis since the summer of 2021. Its main focus today is on analysing the transmission of monetary policy measures through the banking sector to the real economy (see Chapter 6.1). For example, analysing credit developments provides information on whether a monetary policy-induced change in interest rates even reaches households and enterprises via banks, as there may be scenarios in which banks do not pass on policy rate cuts to their customers, for example. If this is the case, lower policy rates would probably have no impact at all on households’ and enterprises’ spending behaviour. Information on monetary policy transmission also helps assess the effectiveness of monetary policy measures beyond adjustments to the traditional policy rate – such as the asset purchase programmes – and to adapt their design to the changing environment.

In addition, monetary and financial analysis focuses on aspects of financial stability. The stability of the financial markets and financial intermediaries (such as banks, insurers and funds) is a key prerequisite for monetary stability. From a monetary policy perspective, in particular, there is the question of whether unsound financial developments will build up in the longer term. These include, for example, excessive debt levels amongst enterprises or households, and speculative price bubbles in the bond, equity or real estate markets. Unsound financial developments such as these can pose serious risks to financial stability. One potential scenario would be an increase in corporate insolvencies, resulting in profitability problems at lending banks and consequently a shortfall in the supply of loans to the economy. Monetary policy makers must include such risks in their deliberations if they have the potential to impact price stability.

Furthermore, monetary and financial analysis investigates whether monetary policy has undesirable side effects for financial stability, as monetary policy can put a strain on financial stability if it contributes to an interest rate level which is persistently too low, for example. Side effects of this kind can be reduced by adjusting the monetary policy instruments if necessary.

6.3 Monetary policy instruments

Monetary policy decisions are made by the ECB Governing Council. The national central banks (NCBs) are responsible for the operational implementation of monetary policy, meaning that, in Germany, responsibility lies with the Bundesbank. Commercial banks maintain the central bank accounts on which they hold their minimum reserves with their respective NCB. Monetary policy refinancing operations (open market operations) and collateral management are also carried out by the NCBs. The ECB may settle money market transactions directly with selected counterparties in exceptional cases.

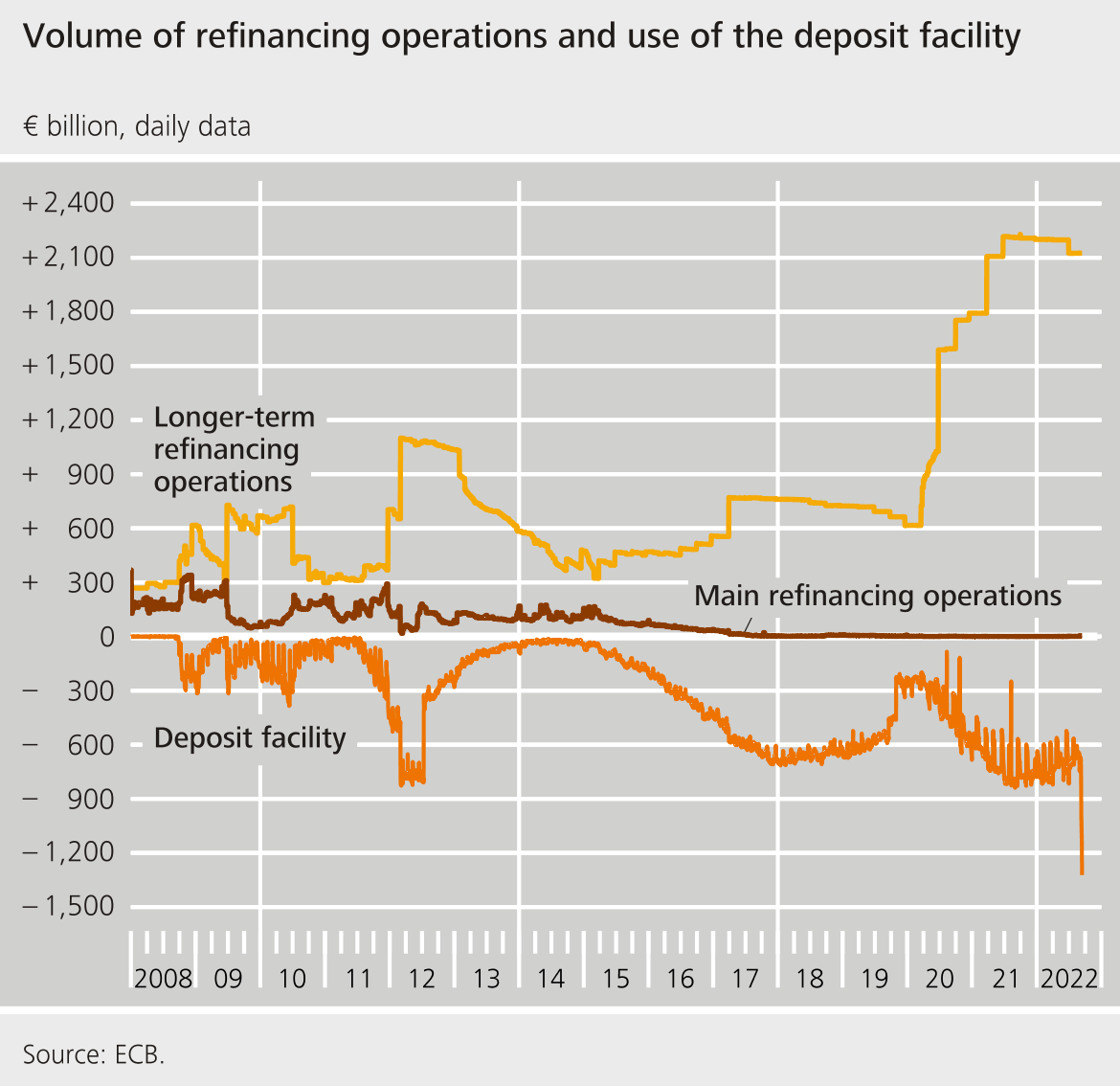

The use of monetary policy instruments by the Eurosystem and the nature of money market management have changed significantly since the onset of the banking and financial crisis in 2007-08. While commercial banks’ need for central bank money was met primarily through short-term main refinancing operations before the crisis, the focus of monetary policy operations is now mainly on longer-term refinancing operations and on the Eurosystem’s ongoing asset purchases.

6.3.1 The minimum reserve requirement

The minimum reserve requirement is part of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy framework. In order to meet this requirement, commercial banks must hold a minimum deposit on their central bank account. This means that banks have a stable need for central bank money. The ECB Governing Council can use the minimum reserve amount required to influence commercial banks’ need for central bank money.

Banks are required to hold minimum balances with the central bank.

Calculating the minimum reserve

The minimum reserve amount required is calculated from the bank’s liabilities.

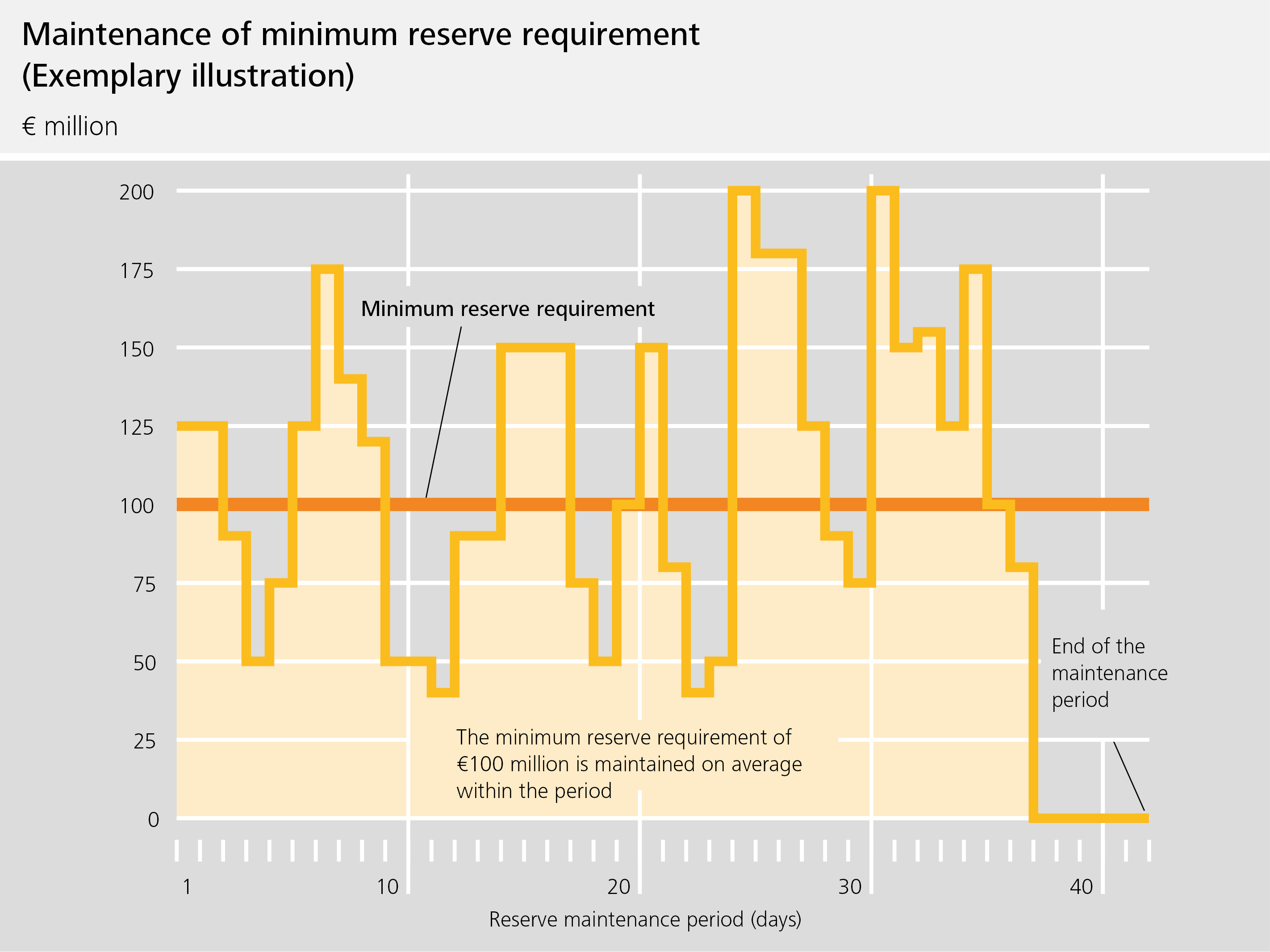

The minimum reserve amount required is calculated from a commercial bank’s liabilities subject to reserve requirements, measured at the end of selected months. For instance, overnight deposits, time deposits and savings deposits are subject to reserve requirements, but also debt securities issued by banks with an agreed maturity of up to two years as well as money market paper. These liabilities subject to reserve requirements are multiplied by the reserve ratio. The commercial bank must hold the resulting amount as a deposit with the central bank. The reserve maintenance period always begins on the Wednesday following the ECB Governing Council’s monetary policy meeting and – depending on the day of the week the meeting takes place – typically lasts 42 or 49 days. The minimum reserve ratio is currently 1%.

The minimum reserve’s buffer function

Banks do not have to maintain the required minimum reserve as a deposit on their central bank account in full every day, but rather only on average over the entire reserve maintenance period. This gives banks flexibility as the reserve balance can act as a buffer: if, for example, customer payment transactions mean that a bank sees an outflow of central bank money on a certain day, this reduces their existing deposit of central bank money and thus also the amount credited for the minimum reserve. The bank is then free to increase its deposit by borrowing in the money market on the same day or to wait to see whether it receives inflows of central bank money over the next few days.

The minimum reserve does not have to be maintained in full at all times, but only on average.

As banks have the option of fulfilling the minimum reserve requirement only on average over the reserve maintenance period, they do not need to be constantly active in the money market. This, in turn, helps to stabilise money market rates, as it means that they do not fluctuate permanently in line with demand. However, each commercial bank must ensure that it has met the minimum reserve requirement on average on the last day of the maintenance period.

Commercial banks’ balances held as minimum reserves on accounts with the national central banks are remunerated. Since mid-December 2022, the interest rate on the deposit facility has been relevant for this purpose. Prior to this, the minimum reserve balances were subject to the (higher) main refinancing rate. The Governing Council decided on this change because, under prevailing market conditions, the deposit rate better reflects those interest rates at which banks can borrow or invest money in the money market.

The amount on a bank’s central bank account in excess of its minimum reserve requirement is referred to as “excess reserves”. These excess reserves are not remunerated.

6.3.2 Open market operations

The Eurosystem uses open market operations to provide central bank money to the banking sector. In particular, it grants loans to commercial banks against collateral. In times of monetary policy normality, the Eurosystem’s monetary policy operations centre around these operations.

In normal times, open market operations are at the heart of monetary policy operations.

If the central bank issues a loan to a commercial bank or purchases its securities, it credits the commercial bank with the corresponding amount in the form of a transferable deposit on its central bank account. Central bank money is created, which the commercial bank can use. If the commercial bank repays the loan or purchases securities from the central bank, the commercial bank’s transferable deposit with the central bank is reduced by the corresponding amount. Thus, the central bank money that was previously created ceases to exist again.

The central bank may purchase securities outright (outright transactions) or for a specific period only (reverse transactions). In the case of reverse securities transactions, the central bank purchases securities from commercial banks, but these banks must commit to repurchasing the securities after a certain period of time (e.g. after one week). Such open market transactions are called “repurchase agreements”, or “repos” for short. These short-term operations make it easier for the Eurosystem to change the volume of central bank money provided and the corresponding interest rate at short notice. In contrast to outright purchases and sales, repos have no direct impact on prices in the securities markets.

Main refinancing operations

The interest rate for main refinancing operations is the most important key interest rate.

Under normal circumstances, the Eurosystem’s main tool for providing central bank money is short-dated reverse transactions. These main refinancing operations have a maturity of seven days. When deciding the allotment for new operations, the Eurosystem can take into account a change in commercial banks’ need for central bank money – for example, because the economy needs more cash as a result of Christmas shopping. The interest rate for the main refinancing operations (main refinancing rate) is the Eurosystem’s most important key interest rate. If the ECB Governing Council raises this policy rate, this is often referred to as a “tightening” of monetary policy; a cut in the policy rate is referred to as the “loosening” of monetary policy.

Longer-term refinancing operations

The Eurosystem uses longer-term refinancing operations to provide banks with central bank money for one month or longer. In response to the banking and financial crisis of 2007-08, the Eurosystem significantly expanded the share of longer-term central bank money for the first time, as banks were no longer granting unsecured loans to each other. The longer-term refinancing operations provided the banking sector with sufficient central bank money. The maturities of these operations were extended to up to four years.

In order to increase bank lending to the private sector and improve the functioning of the transmission mechanism, the ECB Governing Council conducted a series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) between September 2014 and November 2021. The basic idea behind the TLTROs was that the more loans commercial banks granted to the non-financial sector, the more favourable the interest rate terms of the TLTROs became

In response to the coronavirus crisis, additional longer-term refinancing operations were announced in March 2020, and the “pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations” (PELTROs) were decided on in April 2020. These were designed to ensure the smooth functioning of the money markets during the pandemic.

Fine-tuning operations

The Eurosystem can conduct fine-tuning operations to respond to unexpected fluctuations in the need for central bank money. Such operations can be used to provide or absorb central bank money in the short term in a number of ways. These measures aim to counteract undesirable fluctuations in interbank rates in the money market.

Structural operations

Structural operations are intended to influence commercial banks’ need for central bank money over the long term. If particular developments mean that banks’ reliance on refinancing operations is low, monetary policy instruments will no longer take effect as they normally would. In this case, the Eurosystem could, for example, permanently absorb commercial banks’ central bank money by issuing them with certificates for its own debt, as banks are required to pay the purchase price in central bank money. This means that commercial banks are once again more dependent on the Eurosystem’s refinancing operations to cover their needs and that monetary policy instruments become more effective again.

Procedures for tender operations

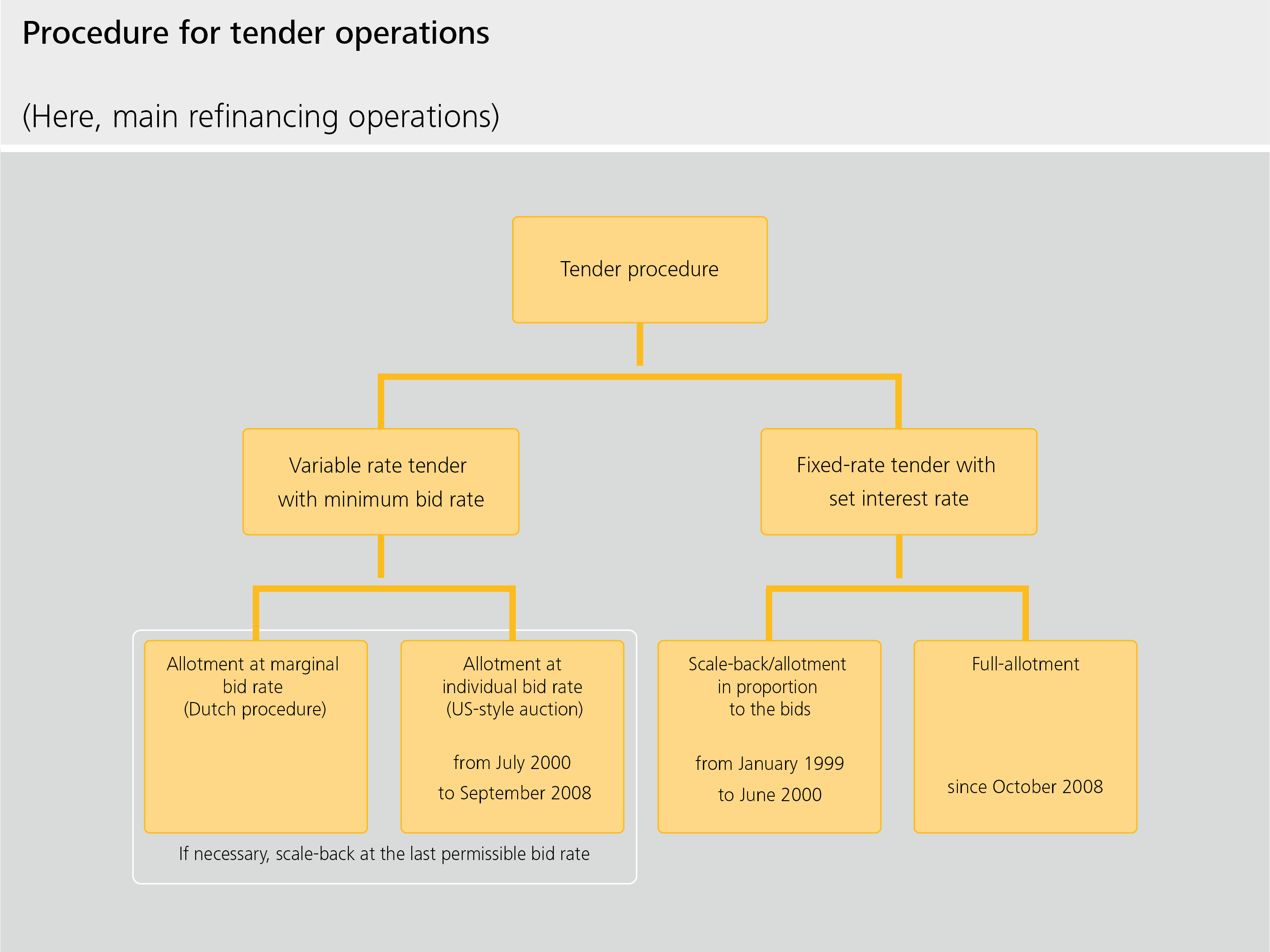

The Eurosystem executes its open market operations on the basis of either tenders or bilateral procedures (directly with counterparties). As a general rule, the Eurosystem uses tenders, which take several forms.

Tenders are used to “auction” central bank money.

In variable rate tenders with minimum bid rates, the Eurosystem specifies in advance the total operation volume to be allotted and the minimum interest rate at which commercial banks must place their bids in order to be taken into consideration in the auction. Commercial banks then submit their bids in a sealed bid procedure, meaning that no bidder knows how much the other auction participants have bid. Each bank states the amount of money it wants to transact with the central bank and the interest rate at which it wants to enter into the transaction. The Eurosystem examines all of the bids and then lists them in descending order, i.e. the banks offering the highest interest rates are considered first, and then bids with successively lower interest rates are accepted until the Eurosystem’s total allotment volume has been exhausted. Bids at the lowest interest rate level accepted may only be satisfied pro rata. For variable rate tenders with minimum bid rates, banks either all pay the same allotment interest rate – the single rate (Dutch) auction – or the interest rate offered in their individual bid – the multiple rate (American) auction.

Until the autumn of 2008, the Eurosystem typically conducted its main refinancing operations on a variable rate tender basis with minimum bid rates and limited allotment volumes using the American auction format.

An alternative auction procedure is the fixed rate tender, in which the interest rate and the total amount of central bank money to be allotted are specified in advance. In their bids, the banks only state the amount of money they wish to transact with the central bank at the fixed interest rate. If the aggregate amount bid exceeds the total amount of central bank money to be allotted, the individual bids are satisfied pro rata.

Following the onset of the banking and financial crisis in 2007-08, the interbank market ceased to function as smoothly as it had in the past. Many banks feared that they would suffer losses if one of their counterparties were to become illiquid or insolvent overnight and were therefore reluctant to lend to each other. In order to ensure that this development did not result in a large number of banks experiencing simultaneous liquidity shortages, the Eurosystem switched to fixed rate tenders with full allotment for its refinancing operations in October 2008. In these operations, commercial banks receive any amount of money they wish to transact with the central bank at an interest rate set by the ECB Governing Council, provided that they can furnish sufficient collateral that meets Eurosystem requirements.

Eligible collateral

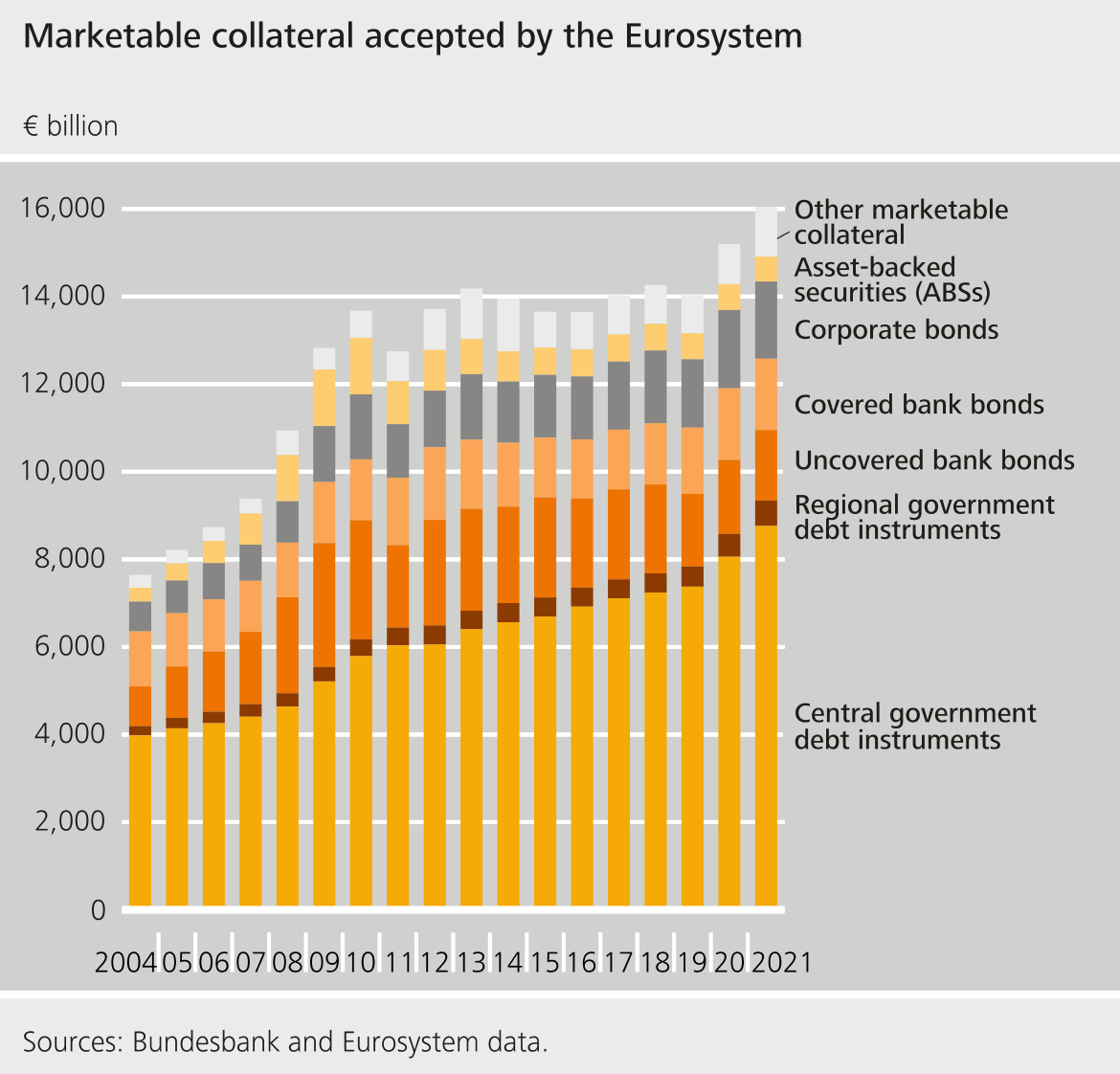

In order to provide the central bank money needed by the banks, the Eurosystem lends to commercial banks via its refinancing operations. To obtain this credit, they need to put up assets as collateral. This is to protect the Eurosystem against potential losses arising from its monetary policy operations: if a bank fails to repay the loan, the Eurosystem can recoup its losses by selling off the underlying assets. Once the Eurosystem has accepted an asset as collateral, it is classified as “eligible”.

The collateral framework consists of assets that can be traded on securities markets, such as bonds of a certain credit quality, as well as non-marketable assets, such as banks’ credit claims on their customers.

The Eurosystem measures the value of underlying assets on a regular basis. The eligibility of assets as collateral for refinancing operations is determined not by their nominal value but by their market value less a haircut. If the underlying assets lose value during the term of the loan, the bank will need to furnish additional collateral.

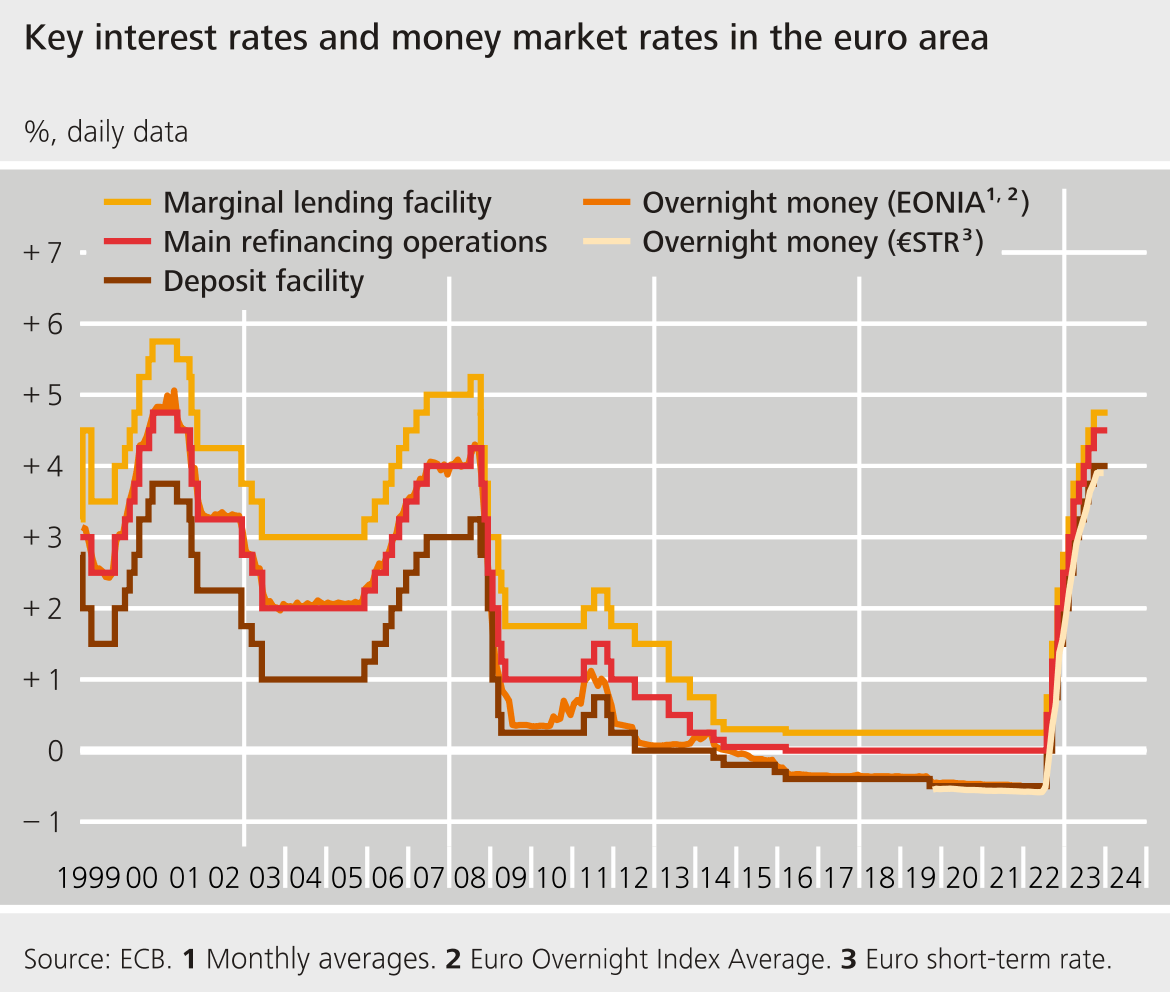

6.3.3 Standing facilities

In addition to open market operations, banks can obtain central bank money from the Eurosystem (marginal lending facility) or deposit money with the Eurosystem (deposit facility) in the short term. Commercial banks can make use of these standing facilities at any time on their own initiative and at their own discretion. The interest rates on the two standing facilities are also key interest rates of the Eurosystem. They form an interest rate corridor around the main refinancing operations rate, with the market interest rates at which banks lend to each other (interbank lending) generally being somewhere within this corridor.

The two interest rates on the standing facilities are also key Eurosystem interest rates.

Marginal lending facility

The marginal lending facility rate serves as the ceiling…

The marginal lending facility is used by commercial banks to cover their short-term needs for central bank money by taking out an “overdraft” with the Eurosystem. Just like liquidity provided in other refinancing operations, this credit is granted against the submission of collateral. Credit granted under the marginal lending facility must be repaid the next day.

The marginal lending facility rate is normally higher than the main refinancing operations rate and generally serves as the ceiling for the overnight interest rate corridor. This is because no bank with sufficient collateral would pay another bank a higher interest rate for overnight credit than it has to pay to obtain overnight liquidity from the central bank.

Deposit facility

… and the deposit facility rate serves as the floor for the interest rate corridor in the interbank market.

Banks can use the deposit facility to deposit excess liquidity overnight in a special account held with the central bank, remunerated at a fixed interest rate. This interest rate is lower than the main refinancing operations rate applicable at any given time. The deposit facility rate generally serves as the floor for the overnight interest rate corridor and thus prevents this rate from dropping sharply. This is because, under normal circumstances, no commercial bank would lend central bank money to another bank at a lower interest rate than can be obtained on its deposit with the central bank.

Commercial banks usually try to lend their excess central bank money to other banks in the money market. As the deposit facility rate is normally lower than the overnight money market rate, banks had no incentive to make great use of the deposit facility prior to the onset of the financial and sovereign debt crisis. This changed following the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007-08. Initially, for fear of their counterparties failing, banks were opting to deposit excess funds with the central bank at a lower interest rate rather than lend to other banks at higher rates. In addition, since the start of the Eurosystem’s large-scale asset purchases in 2015 and the associated drastic increase in excess liquidity in the banking sector, a large amount of central bank money has been deposited in the deposit facility.

Money market management

In times of monetary policy normality, the Eurosystem provides the banking system with precisely the amount of central bank money that it needs by conducting its main refinancing operations. Central bank money is subsequently traded between commercial banks in the money market. The interest rate on overnight money (overnight liquidity from the central bank) is thus close to the main refinancing operations rate. This, in turn, enables the Eurosystem, by raising or lowering the main refinancing operations rate, to also steer the interest rate on overnight money and thereby indirectly influence all other market interest rates.

If, on the one hand, the Eurosystem were to provide less central bank money than the banking system needed, banks would have to make up for the shortfall by using the marginal lending facility, which charges a higher interest rate (and is thus more expensive). This would generally raise the overnight interest rate well above the main refinancing operations rate, meaning that it would no longer be the “anchor” for interest rates on overnight money in the money market or other market interest rates.

If, on the other hand, the banking system were provided with excess liquidity, money would flow into the deposit facility. This would generally cause the overnight interest rate (EONIA until 2021, now €STR) to fall below the main refinancing operations rate – possibly as low as the deposit facility rate. In the secured money market, the interbank interest rate may even be slightly lower.

6.3.4 Monetary policy asset purchases

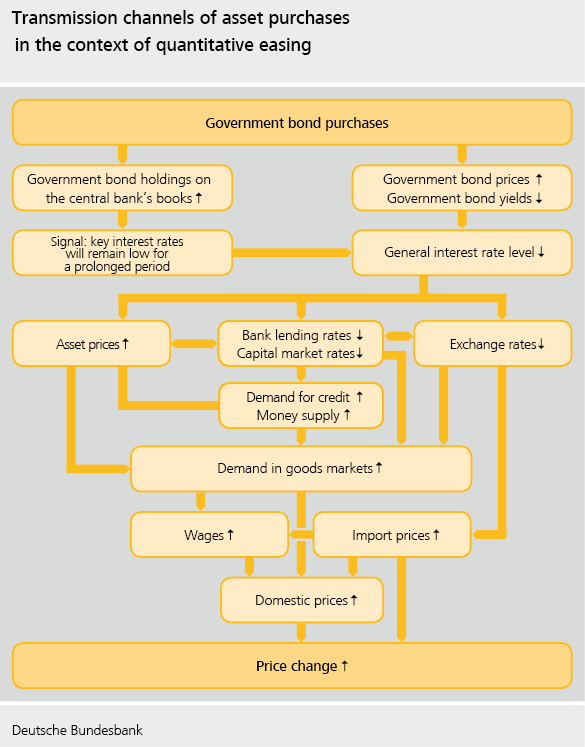

From 2013 to 2020, the inflation rate in the euro area was significantly below 2% at times. Accordingly, the ECB Governing Council repeatedly cut the key interest rates in order to bring the inflation rate back up to its target. At the beginning of 2016, the main refinancing operations rate reached 0% and remained at this level until the summer 2022. Even with key interest rates of 0%, it is possible to create monetary policy stimuli. For example, the central bank can influence the market interest rate level via quantitative easing (QE). It does so by purchasing large volumes of assets (generally bonds).

How asset purchases work

Asset purchases have two main effects. First, central bank money is created when assets are purchased, as central banks pay for them in central bank money. This increases the volume (quantity) of central bank money, which generally increases banks’ scope for lending. Second, the higher demand for assets drives up their market prices. As bond prices rise, bond yields, i.e. the total return they generate, fall. This is because the return an investor receives when a bond reaches maturity derives – in addition to the interest paid – from the difference between the now higher price and the redemption amount determined in advance. Ultimately, these lower yields also lower the general level of interest rates. As a result, a similar effect to that of a traditional policy rate cut is produced, referred to as monetary policy easing. The term “quantitative easing” is derived from the two effects described.

Asset purchase were intended to lower long-term interest rates in order to achieve the price stability target.

In addition, the lower interest rate level stemming from quantitative easing tends to lead to capital outflows to countries where the interest rate level is higher. Capital outflows of this kind cause the domestic currency to depreciate (falling demand for the domestic currency brings about a decline in the exchange rate), which in turn stimulates exports. This, too, invigorates domestic economic activity and tends to cause prices to rise. As a result, quantitative easing can cause the inflation rate to rise and move towards the target.

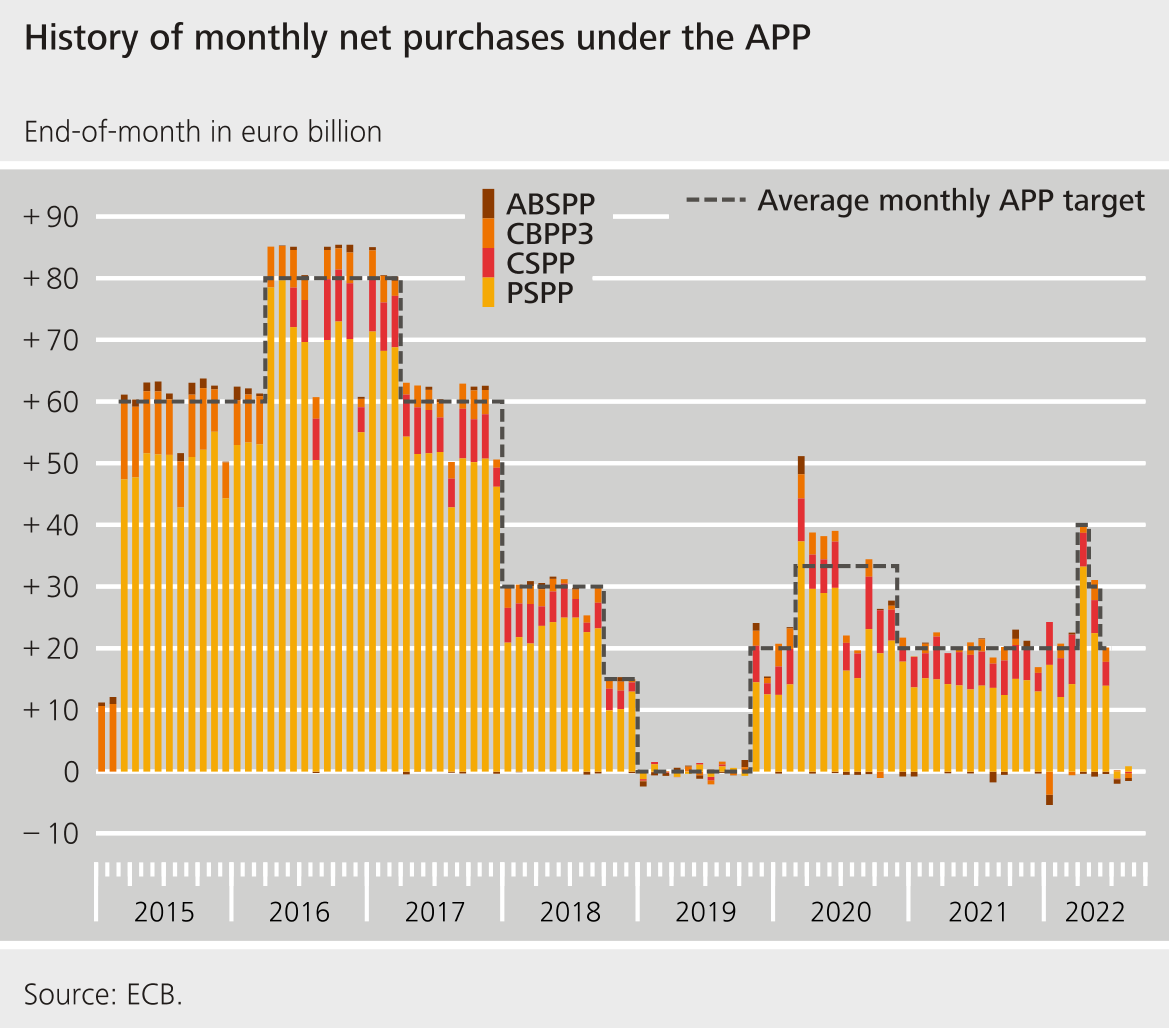

Monetary policy asset purchase programmes of the Eurosystem

In January 2015, the ECB Governing Council decided to embark on quantitative easing in the euro area as well through its asset purchase programme (APP). As a result, the Eurosystem made large-scale purchases of bonds from private as well as government and public issuers, with the latter accounting for the lion's share at just over 80% of the purchase volume.

- Covered bond purchase programme 3 (CBPP3)

- Asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP)

- Public sector purchase programme (PSPP)

- Corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP)

Of these sub-programmes, the largest purchase volume is attributable to the PSPP (i.e. purchases of bonds from government and public issuers).

The largest purchase volume is attributable to the PSPP.

Of the government bond purchases and reinvestments of principal payments from maturing bonds under the PSPP, 80% are conducted by the national central banks. The NCBs focus here on public sector bonds issued in their home country. The amount purchased by each national central bank is determined based on their fully paid-up subscriptions to the ECB’s capital, meaning that the Bundesbank’s share of these bond purchases currently stands at around 26.4%. Any losses that arise are borne by the NCBs themselves. The remaining 20% of the purchase volume is comprised equally of the ECB’s share of asset purchases and the purchases of securities by European institutions. Any losses incurred on this 20% would be shared.

Monthly net purchases under the APP

The monthly net purchase volumes under the APP were adjusted regularly. Starting at €60 billion, they varied from between €80 billion to €15 billion from phase to phase between March 2015 and June 2022. Purchases under the APP were even temporarily suspended for just under one year. Overall, Eurosystem holdings of securities purchased under the APP for monetary policy purposes rose to just over €3.4 trillion.

Under the APP, the Eurosystem purchases large volumes of assets.

In order to eliminate the possibility of direct government financing by the Eurosystem, government bonds are purchased exclusively on the secondary market. This is the market in which investors trade bonds that have already been issued, e.g. a stock exchange. The Eurosystem may therefore purchase a newly issued government bond only after a given grace period has passed. At the same time, certain rules apply to government bond purchases made under the APP. For example, the purchase volume may not exceed one-third of any given issue or of a euro area country’s total bond issuance. Moreover, governments must meet a certain minimum credit quality threshold.

The Governing Council of the ECB has decided to discontinue the net purchases under the APP as at July 2022. Since then, only the repayment amounts of maturing bonds have been reinvested. At the same time, the Governing Council has announced that it will use a Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) if necessary. When needed, the Eurosystem purchases bonds under the TPI in order to counteract unwarranted and disorderly yield developments in the sovereign bond markets of the Member States. This is intended to support the effective transmission of monetary policy impulses in all euro area countries.

In the wake of the coronavirus crisis, the ECB Governing Council decided in March 2020 to launch a temporary pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) to complement the APP. This non-standard monetary policy measure served to counter the risks to monetary policy transmission caused by the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and to achieve the Governing Council’s avowed monetary policy objective. In addition to, and separately from, the ongoing APP, bond purchases of just over €1,700 billion were made under the PEPP. Net purchases under the PEPP were discontinued at the end of March 2022. Since then, only those contributions from maturing bonds in the PEPP portfolio have been reinvested.

As under the APP, the PEPP used the NCB capital key as the benchmark for allocating purchases across jurisdictions. However, the purchases were conducted in a more flexible manner to allow for fluctuations in the distribution of purchase flows over time, across asset classes, and among jurisdictions. The same rules for risk sharing and assumption of any losses applied to the PEPP as to the APP: the risks for 20% of the purchases were shared among the NCBs, whilst the risks for the other 80% of purchases were assumed by each NCB in accordance with the capital key.

The pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) was initiated to counteract the effects of the coronavirus crisis.

Outright monetary transactions (OMTs)

As the sovereign debt crisis intensified in the summer of 2012 and the creditworthiness of various euro area Member States was called increasingly into doubt, the Eurosystem initiated a programme of targeted purchases of bonds issued by specific euro area Member States, known as outright monetary transactions (OMTs), in September 2012. Its aim was to allow government bonds to be purchased in unlimited amounts, as needed, to restore investor confidence in the creditworthiness of the affected Member States, which had been massively shaken at the time.

The prerequisite for the purchase of government bonds under the OMT programme is that the country in question agrees to adjust its economic policies following a European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) or European Stability Mechanism (ESM) programme (conditionality). The OMT programme has been in effect since the autumn of 2012. However, the Eurosystem has not purchased any bonds under the programme so far. Merely the statement that it was willing to do so on a large scale was sufficient to calm the sovereign bond markets.

6.3.5 Forward guidance

Using forward guidance, the central bank aims to reduce uncertainty about the future course of monetary policy.

In central bank jargon, forward guidance is a communication strategy that involves the central bank providing the public with specific information about the longer-term orientation of its monetary policy. The central bank uses forward guidance in an effort to reduce uncertainty about the future course of monetary policy and in doing so steer economic agents’ expectations.

However, forward guidance should not be seen as an unconditional promise with regard to future monetary policy measures either. In fact, when applying forward guidance, the Governing Council reserves the right to change its envisaged monetary policy in the event of unexpected developments, should this be necessary in order to maintain price stability.

6.4 Backing up monetary policy

The Eurosystem’s express primary objective is to safeguard price stability. But monetary policy operates in an environment in which the decisions of other economic participants – such as governments, trade unions and enterprises – also influence prices. For instance, a government’s fiscal and economic policy affects economic developments and consequently price movements. Wage policy likewise has an impact.

Monetary policy cannot safeguard price stability on its own. It needs to be accompanied by stability-oriented economic, fiscal and wage policies. The Eurosystem’s course of stability therefore requires broad support from other economic policymakers, such as the respective governments and social partners.

Stability-oriented fiscal policy is of particular importance

A stability-oriented monetary policy needs to be accompanied by a stability-oriented fiscal policy, in particular. If public finances are not sound, there is a risk of conflicts arising between fiscal and monetary policy that could jeopardise the objective of monetary stability. The higher the level of government debt, the greater the risk. Specifically, as sovereign debt rises, political pressure grows on the central bank to make the financial burdens (interest and repayments) associated with public debt more bearable by keeping interest rates as low as possible and devaluing debt in real terms through “a little more inflation”. If, by contrast, government fiscal policy pursues a stability-oriented course, this conflict is nipped in the bud before it even arises. This then makes it easier for the central bank to safeguard price stability.

The importance of government for monetary policy stems not only from its fiscal policy but also from the fact that it accounts for a significant share of aggregate demand. It can raise this demand significantly in the short term, if necessary by means of credit-financed spending programmes. Moreover, government can influence the income of households and enterprises through its tax policy and through public sector wage agreements – thereby supporting or counteracting the central bank’s objective

Fiscal, tax and economic policy therefore have a major impact on economic activity and, as a result, on price changes. Monetary policy’s task becomes far harder if, in particular, these policy areas act in a procyclical manner, i.e. if they reinforce the business cycle and therefore also price movements rather than countering them. This would be the case, for example, if the government were to provide government subsidies for housing construction with the construction industry already at capacity. This would fuel additional demand, but the housing supply would not be able to expand quickly enough. As a result, prices would rise further.

Social partners with a particular responsibility for stability

Social partners also have a particular responsibility in terms of their wage policies. While it is understandable that employees would want higher wages to compensate for rising prices, excessive wage increases may lead to further rises in prices. If enterprises pass on higher wage costs to consumers in the form of higher product prices, the wage increases are ultimately for nothing. More stringent monetary policy measures, which are bound to have a negative impact on aggregate growth and employment, are generally required to stop an inflationary wage-price spiral of this kind.

DOWNLOAD MATERIAL

FEEDBACK

Key points:

- The central bank’s monetary policy does not directly influence price developments within an economy. Instead, it has an indirect impact on aggregate demand, thereby indirectly influencing price developments.

- The starting point for monetary policy is commercial banks’ need for central bank money. In order to serve this need, the central bank usually lends to the commercial banks. Banks that do not obtain central bank money from the central bank themselves secure the funds they need in the money market.

- The interest rate on the provision of central bank money affects all other interest rates in the financial system. That is why it is known as the policy rate. By adjusting its policy rate, the central bank can influence price developments and, in doing so, safeguard monetary stability.

- The process that describes how a change in the policy rate ultimately affects price developments is called the transmission mechanism. The transmission mechanism is complex, meaning that the impact of a change in the policy rate is not always clearly foreseeable.

- The ECB Governing Council makes monetary policy decisions based on two interdependent streams of analysis: economic analysis and monetary and financial analysis (integrated analytical framework).

- Banks are required to hold a minimum deposit with the central bank. The level of these minimum reserves is determined based on the bank’s liabilities subject to reserve requirements.

- The Eurosystem’s monetary policy instruments influence market interest rates and thus commercial banks’ lending. The Eurosystem’s traditional monetary policy instruments are open market operations (primarily the main refinancing operations and longer-term refinancing operations) and its standing facilities.

- The marginal lending facility enables banks to obtain central bank money in the short term subject to how much collateral they possess. They can deposit excess central bank money overnight in the central bank’s deposit facility.

- The main refinancing operations rate is the most important of the ECB’s three key interest rates. The interest rates on the two standing facilities constitute the ceiling and floor for the overnight interest rate corridor.

- Even with key interest rates of 0%, it is possible to create further monetary policy stimuli. For example, the central bank can purchase large volumes of bonds and thereby influence the market interest rate level (quantitative easing).

- Given the multitude of factors affecting price developments, monetary policy throughout the euro area needs to be accompanied by stability-oriented fiscal, economic and wage policies.

Chapter overview

Overview publications

Important links

- © Deutsche Bundesbank

- Privacy policy

- Imprint

- Declaration on Accessibility